WWF hopes to find $60 billion growing on trees

WWF hopes to find $60 billion growing on trees

The carbon credits scheme would make WWF and its partners much richer, but with no lowering of overall CO2 emissions, writes Christopher Booker .

By Christopher Booker

Published: 4:53PM GMT 20 Mar 2010

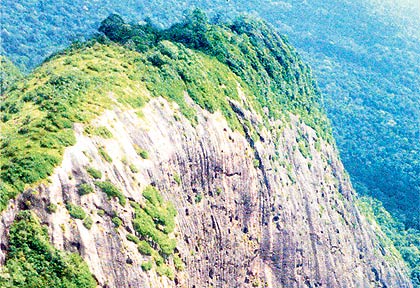

Tumucumaque in northern Brazil has been designated a ‘carbon sink’

If the world’s largest, richest environmental campaigning group, the WWF – formerly the World Wildlife Fund – announced that it was playing a leading role in a scheme to preserve an area of the Amazon rainforest twice the size of Switzerland, many people might applaud, thinking this was just the kind of cause the WWF was set up to promote. Amazonia has long been near the top of the list of the world’s environmental concerns, not just because it includes easily the largest and most bio-diverse area of rainforest on the planet, but because its billions of trees contain the world’s largest land-based store of CO2 – so any serious threat to the forest can be portrayed as a major contributor to global warming.

If it then emerged, however, that a hidden agenda of the scheme to preserve this chunk of the forest was to allow the WWF and its partners to share the selling of carbon credits worth $60 billion, to enable firms in the industrial world to carry on emitting CO2 just as before, more than a few eyebrows might be raised. The idea is that credits representing the CO2 locked into this particular area of jungle – so remote that it is not under any threat – should be sold on the international market, allowing thousands of companies in the developed world to buy their way out of having to restrict their carbon emissions. The net effect would simply be to make the WWF and its partners much richer while making no contribution to lowering overall CO2 emissions.

Related Articles

· G20 summit: Green movement labels G20 a missed opportunity to tackle global warming

WWF, which already earns £400 million yearly, much of it contributed by governments and taxpayers, has long been at the centre of efforts to talk up the threat to the Amazon rainforest – as shown recently by the furore over a much-publicised passage in the 2007 report of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The IPCC’s claim that 40 per cent of the forest is threatened by global warming, it turned out, was not based on any scientific evidence, but simply on WWF propaganda, which had wholly distorted the findings of an earlier study on the threat posed to the forest, not by climate change but by logging.

This curious saga goes back to 1997, when the UN’s Kyoto treaty set up what is known as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). This allowed businesses in the developing world that could claim to have reduced their greenhouse gas emissions to make billions of pounds by selling their resulting carbon credits to those firms in the developed world which, under the treaty, would be obliged to cut their emissions. In 2001 the parties to Kyoto agreed in principle that trees in the southern hemisphere could be counted as “carbon sinks” for the benefit of CO2 emitting firms in the northern hemisphere. In 2002, after lengthy negotiations with WWF and other NGOs, the Brazilian government set up its Amazon Region Protected Areas (Arpa) project, supported by nearly $80 million of funding. Of this, $18 million was given to the WWF by the US’s Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, $18 million to its Brazilian NGO partner by the Brazilian government, plus $30 million from the World Bank.

The aim was that the NGOs, led by the WWF, should administer chunks of the Brazilian rainforest to ensure either that they were left alone or managed “sustainably”. Added to them, as the largest area of all, was 31,000 square miles on Brazil’s all but inaccessible northern frontier; half designated as the Tumucumaque National Park, the world’s largest nature reserve, the other half to be left largely untouched but allowing for sustainable development. This is remote from any part of the Amazonian forest likely to be damaged by loggers, mining or agriculture.

So far all this might have seemed admirably idealistic. Despite the international agreement that forests could be counted as carbon sinks, there was as yet no system in place whereby the CO2 thus “saved” could be turned into a saleable commodity. In 2007, however, the WWF and its allies in the World Bank launched the Global Forest Alliance, with start-up funding of $250 million from the Bank, to work for what they called “avoided deforestation”. A conference in Bali, under the auspices of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which administers the CDM, agreed to a scheme called REDD (reducing emissions for deforestation in developing countries). Hailed as “the big new idea to save the planet from runaway climate change”, this set up a global fund to save vast areas of rainforest from the deforestation which accounts for nearly a fifth of all man-made CO2 emissions.

But still there was no mechanism for turning all this “saved” CO2 into a money-making commodity. The WWF now, however, found a key ally in the Woods Hole Research Center, based in Massachusetts. Not to be confused with the nearby Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, a bona fide scientific body, this is in fact a global warming advocacy group, headed by a board which includes fund managers responsible for billions of dollars of private investments.

In 2008, funded by $7 million from the Moore Foundation and working in partnership with the WWF on the Tumucumaque project, Woods Hole came up with the formula required: a way of valuing all that carbon stored in Brazil’s protected rainforests, so that it could be traded under the CDM. The CO2 to be “saved” by the Arpa programme, it calculated, amounted to 5.1 billion tons. Based on the UNFCCC’s valuation of CO2 at $12.50 per ton, this valued the trees in Brazil’s protected areas at over $60 billion. Endorsed by the World Bank, this projection was presented to the UNFCCC.

But two more obstacles had still to be overcome. The first was that the scheme needed to be adopted as part of REDD by the UNFCCC’s 2009 Copenhagen conference, which was supposed to agree a new global treaty to follow Kyoto. This would allow all that “saved” Brazilian CO2 to be turned into hard cash under the CDM scheme.

The other was that the US should adopt a “cap and trade” scheme, imposing severe curbs on the CO2 emitted by US industry. This would boost the international carbon market, sending the price soaring as US firms flocked to buy the credits that would allow them to continue emitting the CO2 they needed to survive.

As we know, the story hasn’t turned out as planned. Amid the shambles at Copenhagen in December, all that could be saved of the REDD proposals was an agreement in principle, with the hope of reaching detailed agreement in Mexico later this year. Also lost in the scramble to save something from the wreckage was the small print that guaranteed the rights of indigenous peoples in rainforests, whose way of life – to the concern of groups such as Survival International and the Forest Peoples Programme – has already been severely damaged by REDD-inspired schemes elsewhere, such as in Kenya and Papua New Guinea.

Just as alarming to the WWF and its allies, who were hoping to make billions from Brazilian forests, has been the failure of the US Senate to approve the cap and trade bill championed by President Obama. Since the EU has excluded the rainforests from its own cap and trade scheme, bringing the US into the net is vital for the WWF’s hopes of finding “money growing on trees”. The price of carbon on the Chicago Climate Exchange has just plummeted to its lowest-ever level, 10 cents a ton.

The WWF’s dream has been thwarted – but the revelation that it could even be party to such a scheme may have considerable influence on the way this richest of all environmental campaigning groups is viewed by the world at large.