Jan 29

20170

Carbon Markets | REDD, Nature Conservancy, United Nations

"Natura Capital" Arizona Arizona Audubon BHP Billiton BirdLife International Carbon Offsets Commodification of the Commons DoD Ecological Economics Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) Ecosystem Services Externalities financialization of nature International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Millennium Ecosystem Assessment REDD Resolution Copper Mining (RCM) Rio Tinto Sonoran Institute (SI) The International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) The National Audubon Society The Nature Conservancy USDA Walton Family Foundation

The Resolution Copper Land Grab: How Environmental NGOs Expand Green Capitalism

January 28, 2017

People were outraged at the way the Resolution Copper Mining (RCM) finally achieved their land exchange in Arizona. It was the underhanded way Senator John McCain got the legislation passed that fueled the anger, but what many are not aware of is that the swap may not have been possible without the efforts of certain environmental groups. Conservation efforts functioned as currency for Resolution’s access to land, so the land grab could also be called a green grab. Green grabs are taking place in Arizona and beyond, especially around water. The Resolution Copper land exchange provides us with a way to understand the utility of the partnerships corporations forge to gain access to coveted resources.

The land swap is not yet a done deal. An appraisal to determine the equivalence of the parcels to be exchanged is due to be completed this year, according to the Arizona Daily Sun.

“It’s a big ripoff,” Sandy Bahr, director of the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club said in an interview last year. “The American public is getting chump change in return for this ecological treasure. The lands that are offered aren’t comparable.”

McCain’s website tells a different story:

Under the bill, the Resolution Copper company would give the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management about 5,500 acres of land identified by the Department of the Interior as ‘important’ for conservation, including property near the San Pedro River, an important migratory bird corridor and wetland habitat for endangered species. In exchange for these lands, Resolution Copper would receive about 2,400 acres of Forest Service land for the exploration and development of our nation’s top copper asset.

While the Sierra Club does not back up the claims about how important the lands are for conservation, a few other organizations did. Arguably, the land exchange may not have been possible without the help of some of these big, more corporate-friendly environmental organizations like The Nature Conservancy and Audubon Arizona, who were involved in affirming, and even contributing to the value of the land to be exchanged for Resolution’s intended mine site. This is something Rio Tinto (majority owner of RCM) had learned from in partnering with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Utah and Madagascar to arrange access to land a few years before. Multinational mining companies, Rio Tinto in particular, in partnership with NGOs, have been networking to improve the reputation and legitimacy of global mining activities since the ‘90s.

It’s clear that the quantity of land is disproportionate in the exchange. The acreage offered up to the feds for the trade (see map) is more than double Resolution’s desired area. However, McCain needed to sneak the exchange through in the National Defense Authorization Act to get it passed because the status and importance of the Chi’chil Bildagoteel/Oak Flat area resulted in nearly a decade of failed attempts to get the land exchange accepted prior to December 2014. Clearly, the conservation claims never swayed those with strong opposition to the mine, but they do count for something.

The appraiser is required to use nationally recognized standards to come up with the value of the parcels. But not only does Resolution actually have a voice in who gets the job to appraise the properties, the Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions’ directive is that the appraiser determine only a market value (defined within the document) for the land. This does not seem to take into consideration the cultural, spiritual, historical, and environmental values such as those attributed by opponents of the mining in the Oak Flat/Apache Leap area.

Monetarily, while Rio Tinto spent “more than $18 million buying up” the parcels to exchange, the land to which Resolution Copper gained access could be worth around 7,000 times more – over $130 billion based on copper prices as of early 2015, as a former Florida Representative pointed out in The Nation. Copper prices had fallen, but the current price is back up to near where it was then. There are many other factors to enter into the equation, however. One is that Resolution Copper has directed hundreds of thousands of dollars towards the conservation activities that may have increased the value, even if not the market value, of the exchange lands.

While the promise of jobs seems to play a bigger role in Resolution Copper’s narrative, the exchange may have been unacceptable without the purportedly valuable conservation land tracts. And now that the legislation passed, whether it is truly an equitable exchange or not is irrelevant in some ways because if the appraisal sees those lands as insufficiently valuable, RCM will just have to add more land or cash to the deal.

Yet, the conservation values of the parcels offered up by RCM were necessary, and thusly emphasized, for public and federal acceptance. In addition to meeting the equal value requirement, land exchanges are required to serve the public interest, which includes “protection of fish and wildlife habitats, cultural resources, watersheds, and wilderness and aesthetic values,” and the Forest Service gets the final say.

Some of these NGOs have consulted with Rio Tinto to contribute to an accounting method to rate the quality of land, using something they call “quality hectares” as a metric based on various values such as biodiversity to frame as offsets the land parcels they intended to “donate“.

Although the factors, which some refer to as “ecosystem services,” used for this type of valuation, are currently considered nonmarket values not likely to be used in the appraisal, they clearly were important to RCM in determining the value of their land parcels. “Ecosystem services” is an increasingly popular economic construct used to refer to the benefits ecosystems provide to humans.

It doesn’t seem coincidental that law firm Perkins Coie, who has worked for Resolution Copper, wrote a paper in which they made the following argument:

Over the longer term—and to the extent that appropriate methodology is developed and adopted—the BLM could also use the requirement that it obtain fair market value for use of public lands to ensure consideration of ecosystem services in determining land values and rentals.

Both the Forest Service and the BLM (Bureau of Land Management) have attributed legitimacy to recognizing ecosystem services within policy. Multinational mining companies (especially Rio Tinto) and the involved NGOs have been major players on a global scale in market valuation of ecosystem services as well as ways to profit from them.

Valuation of ecosystem services, even if incorporated into the appraisal process, would likely benefit RCM. Even while “cultural,” and more rarely, “spiritual” ecosystem services can be incorporated into the value of land tracts, the fact that the Oak Flat area is not part of a reservation and is not officially recognized as sacred or culturally important works against those who have a connection with the land such as the San Carlos Apache and others.

RCM and certain NGOs’ preferred approach to environmental problems is through market-based “solutions”, which result in transferring resources into private hands. While this is a land grab, the conservation aspect is significant. RCM will gain ownership of the Oak Flat area (unless stopped) by using as currency the parcels obtained and cultivated as conservation projects. The land swap could therefore be considered a green grab. The book (and article) entitled Green Grabbing defines the process as “the appropriation of land and resources for environmental ends” where “‘Appropriation’ implies the transfer of ownership, use rights and control over resources that were once publicly or privately owned – or not even the subject of ownership – from the poor (or everyone including the poor) into the hands of the powerful.”

Why does all this matter? Aside from having more understanding about why this land exchange is not justified, we can learn from how some NGOs partner with private interests to engage in more green grabbing. The Nature Conservancy facilitates the sale of water offsets to companies such as Coca Cola, for example, based on conservation projects in Arizona. They are also supporting the efforts of big housing developments to legitimize construction where aquifers and the rivers like the San Pedro are at risk. Since Rio Tinto has been so central to the development of payments for ecosystem services programs such as offsets, the early stages of this Resolution Copper land exchange effort may have been the foray of the concept of ecosystem services into Arizona.

San Pedro River and Conflicts of Interest

Although the land exchange involved properties in various areas of Arizona, the one in the San Pedro River basin, the 7B Ranch, is the most relevant here, partly because early legislative support for the exchange related to this river. It is also the largest parcel offered by RCM.

Water conservation at the San Pedro River was made central to the land exchange idea when Rick Renzi, US Congressman from Arizona at the time, drew Resolution Copper into a scandal. Renzi was convicted in 2013 of conspiring with the owner of a piece of land in the San Pedro River basin, “to extort and bribe individuals seeking a federal land exchange…” A combination of his connections with Fort Huachuca, an army installation near the San Pedro, and his desire to have Resolution Copper purchase his friend’s property in the area caused Renzi to assert in 2005, according to Wall Street Journal, that his support of the land exchange

…would hinge in part on whether it helped fulfill a goal to cut water consumption along the San Pedro River… participants in the deal say. Fort Huachuca, a big U.S. Army base nearby, was under court order to cut water consumption, and it had been seeking help to retire farmland near the river. Mr. Renzi has longstanding ties to the base, the economic engine of the area… Resolution proposed buying and handing over to the government thousands of acres of bird and wildlife habitat along the banks of the San Pedro, which would further the water-conservation goal.

Due to the high price, Resolution Copper did not buy this property, but the land was sold to someone else. A different parcel in the San Pedro River basin became part of the exchange, a choice likely influenced by the water conservation needs of Ft. Huachuca, as emphasized by Renzi.

Renzi’s father was a retired army general who had served at Ft. Huachuca and his company (one of the congressman’s top campaign donors) has had major contracts with Ft. Huachuca. In 2003, Renzi had proposed “an amendment to the defense authorization bill, [that] would exempt Ft. Huachuca from responsibility for maintaining water levels in the San Pedro River as called for in an agreement made last year with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” Backed by McCain, it passed in November that year, despite media pointing to the conflict of interest.

Dropping groundwater levels have directly impacted the San Pedro base flow. Ft. Huachuca has faced multiple lawsuits for their impact on the riparian environment due to their groundwater pumping.

McCain has shown that he has invested as well in the fate of Ft. Huachuca in relation to the river. His relationship with Renzi likely had a lot to do with it, but he’s continued his support of the fort in recent years. The state of the San Pedro River makes at least an image of water conservation important to the land exchange even with Renzi’s interests out of the picture.

Various partnerships have developed to address, or more likely greenwash the fort’s impact on the environment. The Department of Defense and Ft. Huachuca had already been working with The Nature Conservancy since at least 1998. Significantly, one of the more recent projects is the Upper San Pedro Partnership (USPP) also involving Audubon Arizona. This came out Renzi’s legislative amendment in 2003 which shifted responsibility for water use away from the fort and onto this broader coalition of the USPP.

Shaping the land swap was a combination of these NGOs’ relationships with Ft. Huachuca specifically around the San Pedro River Basin, and Rio Tinto’s relationships with these NGOs through Rio Tinto’s Kennecott Copper mine in Utah where they partnered with NGOs like The Nature Conservancy and the Audubon Society in the late ‘90s on a wetland offset program required due to the pollution of mining tailings.

Partnerships and Payments

Of course it makes sense that environmental groups be consulted about ecologically important issues. There’s a difference, however, between consultation and granting green credentials to mining companies for dubious conservation efforts when they’ll do more damage in the long run. Taken into consideration, additionally, should be the NGOs’ actions and the financial relationship between NGOs and corporations.

One role NGOs play is in acquiescing to the claim that there is no alternative to a particular mine or other development. Then somehow their pragmatism produces “win-win solutions” to supposedly mitigate mines’ damage (this is giving them the undeserved benefit of the doubt about their own financial interests in partnering with corporations). The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Arizona Audubon, even while denying that they took a position on the land exchange, played integral roles in confirming and even generating some of the value of the various parcels RCM obtained and worked to glorify.

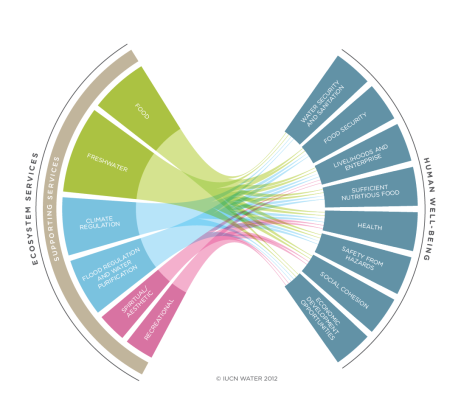

An International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) report described one way NGOs supported RCM (see chart above):

In consultation with conservation specialists, especially the Arizona Audubon Society, RCM rated the conservation value of the parcels in terms of ecosystem condition and priority for conservation in Arizona. In doing so, RCM was able to take a semi-quantitative approach using Rio Tinto’s quality hectares method, to determine whether the parcels represented equivalent or better conservation benefits than the government land.

According to Rio Tinto,

Quality Hectares are Rio Tinto’s current metric for tracking progress towards the [Net Positive Impact (NPI)] target at the global and site levels. A wide range of biodiversity values, including threatened species, rare habitats or non-timber forest products, may be expressed in terms of their quantity and quality.

It could be argued that RCM bought access to the copper ore in Oak Flat by funding NGOs’ conservation attribution of value to the land that RCM had accumulated. NGOs acted as consultants in choosing land parcels and quantifying their value, managed some of those parcels, wrote letters confirming their value, and thereby contributed to legitimizing the exchange.

Rio Tinto/Resolution Copper started funding Arizona Audubon Society in 2003. The mining subsidiary began lobbying for a land exchange in 2005 and in the same year contracted with TNC to manage the land parcel owned by BHP Billiton called the 7B Ranch.

The 7B Ranch was the piece of land in the San Pedro River basin that ultimately became part of the land exchange. Copper companies in Arizona have purchased land not only for mining, but BHP Billiton already owned some land near the San Pedro River prior to the idea for the land exchange, likely for the water rights.

The Superior Sun reported,

Resolution purchased 7B from BHP in 2007 with the intention of including it in an eventual land exchange… David Salisbury, Resolution Copper CEO, said that the company spoke to organizations such as Arizona Audubon and The Nature Conservancy to determine conservation targets that a number of agencies might be interested in…

Although Audubon hasn’t taken a position on the proposed land exchange, they have been on record since 2005 saying that 7B is an ecologically important piece of property…

With the plan in place, Resolution and its conservation partners hope to make 7B a ready-to-use asset for the [Department of the Interior] and the public.

The Tucson Sentinel reported in 2011, “7B Ranch, which contains one of oldest mesquite forests in Arizona, lies near the fragile San Pedro River. In 2007, Resolution Copper agreed to pay The Nature Conservancy $45,000 a year to manage the property.” They also noted the, “$250,000 in grants and donations that Resolution Copper and Rio Tinto have given to the Audubon Arizona since 2003.” Their coverage stated that the Sonoran Institute (SI) was also involved in identifying parcels that would be of value in the exchange.

RCM also supported SI for at least two years (2007 and 2008) and hired SI’s Dave Richins after, as The New Times revealed, he’d been doing work for RCM for a while prior to official employment. Luther Propst of SI authored an opinion column in the Arizona Republic in 2010 in favor of the Resolution Copper mine.

News outlets such as the Tucson Citizen reported in 2005 that, “the Audubon Society, the Nature Conservancy and the Sonoran Institute have all sent [Bruno Hegner, Resolution’s general manager] letters of support.” The Tucson Sentinel wrote that “Leaders of Audubon Arizona and The Nature Conservancy have said they neither support nor oppose the overall plan. But each group has formally attested to the conservation value of the Appleton-Whittell and 7B Ranch parcels, something that Resolution Copper has noted prominently in letters and testimony to Congress.” In 2011, 2012 and 2013, the Arizona chapter of TNC sent letters to legislators reiterating their neutrality on the legislation, but elaborating on the value of the 7B Ranch property. Audubon Arizona had been managing the Appleton-Whittell ranch since the 1980’s. Notably, other Arizona-based Audubon groups (Maricopa and Tucson) have been openly opposed to the mine.

Resolution Copper partnered with Audubon Arizona, TNC, Birdlife International, along with the Salt River Project and others on the Lower San Pedro and Queen Creek Project, described by Birdlife International:

A two-year programme (2006–2007) undertook the development of a bird conservation strategy… It assisted in the provision of detailed biodiversity assessments of the land exchange parcel on the Lower San Pedro River for Resolution Copper Company and with the establishment of baseline data for the mine’s operational biodiversity action planning.

Thanks to the project, the Lower San Pedro River, from “The Narrows” north to the confluence with the Gila River, has been surveyed, nominated and recognised as a state [Important Bird Area (IBA)]. During 2006–2007, existing and newly collected data were compiled and submitted to the Arizona IBA Science Committee, in support of the IBA nomination of the Lower San Pedro River, and the nomination was accepted.

Birdlife International, which Rio Tinto has been working with since 2001 is described as “a global alliance of conservation organisations working together for the world’s birds and people.” One of Birdlife’s main partners is the Audubon Society, a group with which they’ve had overlapping board members.

It is not so difficult to imagine that an “environmental” group, such as Birdlife or TNC would accommodate a mining project considering TNC participated in drilling oil on a property they were supposed to have retired from oil production. Kierán Suckling of the Center for Biological Diversity said that TNC “has shown over and over again its willingness to take corporate money in return for stealing, destroying, or polluting indigenous and poor human communities.” TNC has partnered with many of the most notorious corporations like Exxon, BP, Dow Chemical, and Monsanto along with Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton. Birdlife had also partnered with BP, which may have been a factor in Rio Tinto partnering with the NGO in 2001.

From Greenwashing to Green Markets

Mines have pock-marked the earth, poisoned the land, water, and living beings, displaced communities, and left other destruction in their wake. One of the most notorious mining conflicts forced Rio Tinto to shut down their mine on Bougainville Island of Papua New Guinea in 1989 due to an uprising largely in response to the environmental damage caused by the mine. A lawsuit was filed against Rio Tinto over “racial discrimination and environmental harm, as well as genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity,” arising from the mine and the military response as part of the decade-long civil war instigated by the company. Throughout the 1990’s major tailings containments collapsed each year around the world. Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton have both faced various strikes over working conditions. It’s no wonder they had to fix their reputation in order to do business.

While the Bougainville civil war was still raging, a study that Rio Tinto conducted in 1996 showed that the mining companies could benefit from addressing concern for biodiversity as part of their medium-to long-term business strategy. This may have played a part in the Rio Tinto chairman’s launch of the Global Mining Initiative (GMI) with nine of the largest global mining corporations in 1999. “The drivers for GMI were clear recognition that mining companies had problems of access to land, and access to markets, and cost of capital. The fundamental underlying reason was the reputation of the industry,” said Dr. John Groom, of mining company Anglo American.

Sarah Benabou writes that in 2000,

the GMI started a process of consultation and research known as the Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development (MMSD) project to determine the fundamental orientations that would shape the future of the industry. This project led to the creation of the [The International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM)] in 2002. A few months later, at the Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development, the ICMM and the [International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)] started a joint dialogue on mining and biodiversity ‘to provide a platform for communities, corporations, NGOs and governments to engage in a dialogue to seek the best balance between the protection of important ecosystems and the social and economic importance of mining’ (IUCN 2003: 1).

Benabou’s Making up for lost nature? A critical review of the international development of voluntary biodiversity offsets also describes how mining companies and NGOs at an IUCN/ICMM jointly-organized workshop in 2003 could draw upon each others’ experiences regarding ways to apply a biodiversity offset approach even if it couldn’t be “transposed term-for-term” in other situations. IUCN is one of the oldest and biggest environmental NGOs.

The relationship with Birdlife, initiated by Rio Tinto in 2001 was an early venture into partnerships with such NGOs. According to Rio Tinto, “the partnership has enabled both organisations to deliver outcomes that neither could have achieved as effectively when working alone.”

It would be a mistake to frame this simply as examples of greenwashing in attempt to solve mining companies’ public relations problems and access to land. In the context of the earth’s welfare and diminishing finite resources, the extractive industry and their partners have developed market-based tools like offsets to create new financial strategies. “In this zeitgeist of crisis capitalism, the environmental crisis itself has become a major new frontier of value creation and capitalist accumulation,” writes Sian Sullivan, Professor of Environment and Culture in the UK. The commodification and financialization of so-called natural capital and ecosystem services are central to this process.

The introduction to Nature, Inc. spells it out: “Capitalism now endeavors to accumulate not merely in spite of but rather precisely through the negation of its own negative impacts on both physical environments and the people who inhabit them, proposing itself as the solution to the very problems it creates.” Similarly, co-editor of Nature, Inc., Bram Büscher posited elsewhere, “To believe that nature can be conserved by increasing the intensity, reach and depth of capital circulation is arguably one of the biggest contradictions of our times.”

IUCN, along with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), was involved in the early 1990’s in advancing the concept of ecosystem services, aka environmental services, beginning with their Global Biodiversity Strategy. This was a predecessor to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) completed in 2005, to which IUCN and UNEP also contributed. MA has been considered a game-changer in the way it endeavored to apply a monetary value to ecosystem services; the wide variety of beneficial (to humans) functions deriving from ecosystems, like carbon sequestration and water purification.

One of the biggest payments for ecosystem services (PES) program currently is REDD or Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (the latest version is called REDD+) which Tom B. K. Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Network said could lead to “the biggest land grab of all time.” REDD is a project of IUCN, supported by Rio Tinto (including in its early development). Rio Tinto claims that REDD+ allows them to offset their carbon footprint. The Nature Conservancy, and Birdlife International are proponents of REDD+.

REDD and the carbon trade in general have meant further financialization of nature, involving hedge funds, derivatives, and “a new generation of ‘commercial conservation asset managers’ required to broker these exchanges and revenues,” according to Sian Sullivan. “Conservation investing experienced dramatic growth after 2013, as total committed private capital climbed 62% in just two years from $5.1B to $8.2B,” reported Ecosystem Marketplace recently.

NGOs and negotiations have enabled and structured “new green market opportunities and practices as they orchestrate the social and political relations among various state and non-state actors through which the mechanisms, incentives and legitimating conditions for green grabs are established,” as is argued in Enclosing the global commons: the convention on biological diversity and green grabbing.

Experts from the big NGOs are called upon to design, implement, and/or verify such mechanisms as offsets. While carbon offsets are the most notoriously dubious, mining companies are involved in a variety of other offsets, both voluntary and regulatory.

Buying, Banking, Trading Offsets

In Utah, a land tract Kennecott wanted for storage of their tailings (materials left over from processing of mined substance) was designated as wetlands, which are regulated. So according to a case report put out by The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB),

Kennecott was thus required by U.S. law to offset, or mitigate, the loss of wetlands by the creation of an agreed number and value of habitat units… In 1996, Kennecott Utah Copper Company undertook the cleanup and construction of the 1,011 ha Inland Sea Shorebird Reserve (ISSR) in conjunction with a project to expand its tailings storage.

Kennecott Utah Copper Mine (Rio Tinto)

In addition to the required wetlands offset, Rio Tinto established a “bank” of restored surplus habitat land which, as TEEB explained, referencing an unpublished study, “could be used to offset future impacts on wetlands (584 ha) adjacent to the mitigation site… Credits from the bank can be used by Kennecott or sold to others for wetlands mitigation in accordance with the terms of the Bank Agreement with the US government.” Banking converts wetland habitat properties into assets. Rio Tinto wrote in 2011 that they have, “successfully developed and then sold wetland credits” as part of the ISSR.

Essentially, companies can profit from ostensibly going above and beyond their responsibilities (or having a “net positive impact”) for mitigating the damage they cause through mining. In many cases, profit-driven wetlands banking has been shown to result in a net loss, however.

TNC and National Audubon Society were involved in developing this wetland mitigation plan. The ISSR also became an IBA in 2004 and is part of BirdLife International’s IBA Program.

BirdLife International also endorsed Rio Tinto’s activities across the world in Madagascar. Rio Tinto owns 80% of the QMM (QIT Madagascar Minerals) ilmenite (titanium dioxide) mine in Southeastern Madagascar which started mining in 2005. The mining activities “will remove more than half of a particular type of unique coastal forest.” BirdLife described the benefits of a project implemented by a BirdLife affiliate and supported by Rio Tinto:

The direct payments [for conservation] project aims to strengthen the conservation of Tsitongambarika’s unique and threatened biodiversity, enhance water security for QMM’s mining operations… and maintain ecosystem services essential for regional development.

Rio Tinto is partnered with this affiliate in a biodiversity offset program. Note that other than biodiversity, the benefits of the project are for the mine and/or “regional development” but are subsumed into conservation as well. The biodiversity offsets involve “the financing of, or provision of land for, biodiversity conservation outside of mining zones,” explains PhD candidate in Anthropology, Caroline Seagle. The idea is that aspects of biodiversity are exchangeable (or fungible) with others, so damage to this particular type of forest can be made up for elsewhere.

For aspects of ecosystems to be treated as fungible commodities, their uniqueness and complexity needs to be erased for the sake of market exchange. This “offset ideology” is “premised upon the monetization of nature and market rationality,” writes Seagle, in “Inverting the impacts: Mining, conservation and sustainability claims near the Rio Tinto/QMM ilmenite mine in Southeast Madagascar” (for a similar more accessible version, see “The mining-conservation nexus“).

“Through the paradigm of conservation finance and payments for environmental services (PES), the ‘offset ideology’ is less mitigatory and more compensatory – making up for local damage through land allocation or financial support of nature conservation,” criticizes Seagle.

Similar to Rio Tinto’s wetland banking, these mechanisms are not only intended to compensate for damage, but to create revenue. IUCN wrote in 2011 of Rio Tinto’s further steps in Madagascar to gain from conservation:

Rio Tinto is using established relationships with its biodiversity partners and specifically its relationship with IUCN to explore how ecosystem services can be accurately valued and the implications for corporate risks and opportunities.

For companies like Rio Tinto, robust methods of valuing ecosystem services and the development of well functioning markets for ecosystem services could provide an opportunity to use large non-operational land holdings to create new income streams for Rio Tinto and for local stakeholders and communities, through the sale of ecosystem service credits.

Biodiversity offsets became a primary tool to make headway into areas they wanted to mine. An IUCN document reiterated,

[For some] Multinational companies, whose operations have an impact on biodiversity and for whom license to operate – both formal concessions from governments and social license from communities – are key to business success. Their view of biodiversity offsets is that best practice on biodiversity – possibly including offsets, whether mandatory or voluntary – is important to access land, maintain reputation… and the avoidance of interference and disruption from NGOs and local communities.

The wetlands offsets in Utah and the biodiversity offsets in Madagascar are just two experiences the mining companies could learn from leading up to the Arizona land exchange. While Rio Tinto was mandated to buy wetlands offsets for their Kennecott Utah mine, in the Arizona case, RCM had to do a land exchange to access the Forest Service land, and there seem to be no other mandatory mitigatory steps required of RCM. But they did use ecosystem services to attribute value to the conservation lands, which seemed to have some utility for them.

The land exchange was framed in terms of offsets because it of its purported mitigatory function. In his testimony before the U.S. Senate Sub-Committee on Forests and Public Lands, the President of Resolution stated in 2009, “we believe the exceptional quality and quantity of the non-federal lands that will be conveyed into Federal ownership more than off-set any expected surface impacts to the lands acquired by Resolution Copper” (my emphasis).

The ICMM featured the Arizona land exchange in a 2010 Mining and Biodiversity case studies report, framing it as an offset as well:

Given Rio Tinto’s commitment to a net positive impact to biodiversity, the land exchange presents a unique opportunity to exceed the requirements of trading land of equivalent economic value by ensuring that the land parcels offered in the trade are also of equivalent or greater value for the conservation of biodiversity and provision of environmental services – a biodiversity offset (my emphasis).

The chart from this report (see above) shows the various parcels in Arizona Rio Tinto offered up as “offsets,” along with the their quality valuation, based on consultation with Audubon Arizona and other NGOs.

Again, the biodiversity and environmental services would likely not be accounted for in the official appraisal. However, Resolution’s claim of these voluntary offsets may have contributed to an attempt to prove that the swap is in the public interest.

Conservation Value

“The American public is getting ripped off,” Silver said. “The only land that is of value is the research center’s because it hasn’t been overgrazed, but it’s of no value to the general public because it wouldn’t be open to them, unlike Oak Flat that offers recreational opportunities to the public and is of cultural value to Native Americans,” Silver said.

Many, like Robin Silver, co-founder of the Center of Biological Diversity, as quoted by the Arizona Daily Sun disagree with TNC and Audubon Arizona’s opinions of the exchange parcels. Several environmental groups opposed to the mine detailed the damage the RCM would cause, as well as the poor quality of the exchange sites in their Scoping Comments for the Resolution Copper Mine DEIS.

“The San Pedro is not free-flowing at the 7B Ranch,” Witzeman wrote.

Bob Witzeman, an environmentalist who spent several of his final years fighting against the Resolution Copper mine, commented that the 7B Ranch owned by BHP Billiton was likely purchased for its water rights and “is under no duress for need of protection… There is no danger of mining here, or developing homes here, because it is in a flood plain.”

In earning credit for offsets, protecting a site only counts for something if the site is under threat. This is called additionality. Some states and institutions require additionality as part of offset programs. The “counterfactual,” or what otherwise would have happened without a conservation project such as an offset program, is often difficult to ascertain. As far as the land exchange in Arizona goes, not only do many of the parcels seem of poor quality, especially compared to Oak Flat, it’s likely that there was no imminent threat to the largest parcel, 7B Ranch, nor the Appleton-Whittell parcel which was converted into a research facility in 1968.

This is not to say that conservation efforts are for naught (though there’s evidence that many of the projects, especially when profit-driven are not even effective), or that there is any legal weight to this point, but this needs to be considered. For example, regarding the 7B Ranch, Witzeman wrote, “BHP does own another riverside parcel with riparian habitat. BHP does plan to develop homes in that area, some 35,000 units. As of this time, they have made no commitment to protect this riparian habitat.” The land was still being preserved in 2013 (I was unable to find anything more recent) but the reason given that the real estate development plan didn’t come to fruition was the economic downturn in 2007.

This brings up another problem with offset programs called leakage. “Leakage occurs when environmentally destructive activities… are shifted from the places targeted for conservation to other sites,” explains Kathleen McAfee in Green economy and carbon markets for conservation and development: A critical view. Just one relevant example of leakage is when TNC purchased 500 acres along the San Pedro to retire it from agricultural irrigation only to have the seller begin irrigating a nearby 500 acre plot soon after.

Resolution’s protection of the 7B Ranch at the expense of nearby land can be shown in the case when the Sunzia transmission line project was in the planning stages, and two of the potential routes could have impacted the conservation value of the 7B Ranch. Resolution Copper sent a letter opposing those routes. The Final Environmental Impact Statement shows a somewhat different but nearby route as the BLM preferred alternative. RCM did not comment on other routes that would also affect the region. This not only shows that conservation is only important when it benefits the company, but it also points to another issue that comes up when profit factors into conservation. Scarcity, caused by development, increases the value of conservation products (such as offsets), thereby incentivizing conservation, but also more development.

Sian Sullivan argues that conservation banking is development-dependent. “Indeed, development that produces transformation of habitats is required for conservation credits to attain the prices that will encourage establishment of conservation banks and bankers, thereby generating trade in conservation credits as a funding strategy for conservation management.”

Seagle pointed out that as part of a strategy of sustainability in Madagascar – though applicable in other cases – Rio Tinto is paradoxically creating scarcity of biodiversity while claiming to save it.

Here and Now

The Nature Conservancy’s legitimization of development is not isolated to Resolution Copper, even in Arizona. Water is particularly vulnerable to green grabbing, as water is integral to ecosystem services as well as a necessary resource for industry. Aside from the partnerships with Ft. Huachuca noted above, TNC is also working with Castle & Cooke’s housing development called Tribute in Sierra Vista, as well as El Dorado Holdings’ Vigneto Villages housing development in Bensen, the latter involving a “mitigation parcel” as an offset. Both could be serious threats to the San Pedro and nearby aquifers, and require proof of assured water supplies.

A major threat to aquifers and other surface water in Arizona relates to what’s happening with the Central Arizona Project (CAP) water Arizona has come to depend on (though destructive). Arizona is taking voluntary Colorado River water reductions to delay an official shortage declaration triggered by Lake Mead’s water level. Water officials have been meeting with various leaders in different sectors to arrange voluntary cuts, with a plan to compensate water users (this may involve more market-based “solutions”) for 400,000 AF per year. Resolution Copper has secured a portion of Arizona’s stored water in the form of storage credits, which brings up more issues regarding recovery. RCM expects to also be able to access large quantities of CAP water, but this allocation is in a low priority category, and therefore is subject to cuts. Farmers, tribes, and others are subject to having to forego their share of CAP water, essentially to secure water for the mine (and other mining operations and water bottling, etc). As CAP reductions go into effect, stress on other sources of surface and ground water will increase.

What may be most troubling to readers is that an NGO has been selling water offsets based on watershed restoration projects, to companies like Coca Cola and Intel Corp. While they continue to use massive amounts of water, companies’ “water footprints” are allegedly reduced by voluntarily buying Water Restoration Certificates (WRC) from Bonneville Environmental Foundation (BEF). WRCs supposedly help restore a watershed in partnership with local landowners and big environmental groups like TNC. BEF also sells carbon offsets.

One such project involving TNC and BEF (supported by Walmart heirs’ Walton Family Foundation) is the relatively new Verde River Exchange Water Offset Program. Reading media coverage on this project, you wouldn’t gather that this is part of TNC’s efforts in developing water markets across the globe. Their 2016 report called Water Share: Using water markets and impact investment to drive sustainability says a lot more, revealing that their hypothetical model involves reallocating (selling or leasing) the majority of the “conserved” water from farming (that would otherwise contribute to the aquifer or river but is considered “lost”) to another sector in order to raise revenue to compensate farmers and to profit investors. These small-scale pilot projects may have much bigger implications in the future.

A few recently published papers (funded by the Walton Family Foundation) apply monetary value to and promote payments for ecosystem services of the Colorado River Basin, and suggest unbundling water rights to create a water market in the Western US. Water-marketing may be central to addressing the main obstacle to finalizing a Lower Colorado River basin Drought Contingency Plan – California’s Salton Sea. Arizona aims to resolve remaining tribal water rights claims on the state’s terms and facilitate water marketing. A major US/Mexico water agreement makes water marketing central to multiple aspects of the current and future versions. The Bureau of Reclamation has become involved in water marketing, and things may become even worse under Trump’s administration.

It is concerning that seemingly necessary feel-good projects in water conservation will actually serve capitalism. But there is no denying that there are many examples of this across the world. NGO/corporate partnerships have served to contribute to learning experiences, provide green credentials for mining companies and other development to influence media and decision-makers, and create new mechanisms for access to resources and financial gain.

Standing Rock water protectors’ efforts were evoked in an article on the Ecosystem Marketplace website in which the author declared that 2016 was a year for learning the value of water. The article promoted market-based mechanisms like those developed by TNC. The real lesson to be learned is not that the value of water should be translated into market terms, but instead many have learned that resource appropriation (when not invisible) is backed up by state violence or the threat of it. Those who physically obstruct the Resolution Copper mine, or in any other case, in protest may be treated similarly to the water protectors fighting against DAPL.

See an accompanying page on the San Pedro River for more on that.