REDD ‘Opportunities’ | AMAN

“We want to change this threat to an opportunity”: Interview with Abdon Nababan and Mina Setra

By Chris Lang, 4th July 2010

Interview with Abdon Nababan, secretary general of the Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN – The Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago), and Mina Setra the head of international policy at AMAN. The interview took place in AMAN’s office in Jakarta on 9 June 2010.

REDD-Monitor: Please describe AMAN’s work and explain your position on REDD in general.

Abdon Nababan: AMAN was established in March 1999, in the first congress of Indonesian indigenous peoples. Our main mandate is to recover indigenous rights in all sectors of development, in our law, in our national policy. So if we talk about REDD, we talk about it in a way to reach that mandate: to recover indigenous rights on land, on territories, natural resources, on culture, on political sovereignty and so on. Because we have that objective or goal, nothing else. So we see REDD as either an opportunity or a threat to our goal. In AMAN we see REDD as an opportunity if the result is that before we talk about REDD we have first secured indigenous rights. That’s the meaning of “No Rights, No REDD”.

If we talk about REDD, we don’t talk about the carbon market. We talk about the traditional way that indigenous people protect their forest from deforestation and from forest degradation. They have that way, they have that knowledge. They have that customary right to do that. They don’t have the power to reject threats like forest concessions or mining concessions, that’s why they want the national law, the state law. That’s all they don’t have. In that sense, we believe that REDD is already there. REDD is not a new animal in their territories, because they already have a system to protect the forest.

But REDD as a market scheme, of course that is new. They don’t have any imagination of how carbon can be traded. So we need to clarify this, because this is very important for us. If we talk about REDD, we need to clarify which REDD are we talking about?

REDD-Monitor: Before this Norway-Indonesia deal appeared, what was AMAN’s work on REDD in Indonesia? What kind of work had you been doing on REDD?

Abdon Nababan: We advocate for the rights of indigenous peoples to their customary forest, such as within the national forestry law. That we consider as our work, to advocate the space for indigenous peoples to manage their own resources, their own territories, with their own knowledge, with their own strategies.

So we have been doing that since we were established. We have helped the people to map their community land. We empowered them with critical legal analysis, education and so on. That’s our main mission.

Mina Setra: We had training of trainers for community mapping, how to use GIS so that they can map their territories. We produced material, information about REDD. What is REDD? What is the threat? And we gave that to our community members. We organised training of trainers on carbon trade and REDD, with the communities to strengthen their capacity and knowledge on the issue so they can prepare themselves to deal with it when it comes to their territories

Abdon Nababan: The question is how to prepare our members, the communities, to respond this issue. Because the issue from REDD, for now, is a threat. We want to change this threat to an opportunity. But we need well-trained activists to do that, to change this threat to an opportunity. That’s what we are doing right now.

Mina Setra: One other thing. We just established an Ancestral Domain Registration Agency on 11 March this year. We want to establish a place for indigenous peoples to register their territories. Because for several years, many indigenous territories have been mapped, we have more than two million hectares of indigenous territories that have already been mapped.

Abdon Nababan: It is not recognised, but we want to put the data in the government office.

Mina Setra: The indigenous communities have started to register their territories in this Agency, we also have a website that you can look at (www.brwa.or.id).

REDD-Monitor: Coming on to the Norway-Indonesia billion dollar forest deal, how is AMAN involved in the negotiations? Could you say something about the meeting that you had at the President’s Office.

Abdon Nababan: Actually we are not involved in the negotiations. Of course, as an advocacy group, we try to intervene on both sides. We are not talking in the negotiations, because it’s not our negotiations. It’s the Norwegian government and the Indonesian government negotiating. Of course, Norway asked about our position, but I think we have our global position on REDD. We don’t need to respond to that, because the “No Rights, No REDD” position, is already there. I think, they already put that in their policy even. So we don’t need to do more, except to watch how Norway deals with that.

With the Government of Indonesia, of course, that’s a different intervention. Agus Purnomo, the President’s special staff on climate change, explained the negotiations and said that one of the issues about these negotiations is indigenous peoples rights. I said, it’s not, why? Because the Indonesian government has already done quite a lot about that. That will be the better position for the President to talk about it to Norway. I talked about what the Indonesian government has already produced or released. The Environmental law recognises and protects, respects indigenous peoples rights. The Indonesian government also produced the Coastal Zone and Small Islands Management in 2007, that also recognises, protects and respects indigenous peoples’ rights. So what’s the problem, I asked? We don’t have the definition [of indigenous people], Agus Purnomo said. I explained that the definition is in this law. And that definition is based on AMAN’s work. The government adopted AMAN’s congress decision about that. And the definition is very close to the ILO convention 169. So what is the problem? The problem is the national forestry law. But you can change that, I said. You talk with the President. Come on.

If can we recognise, protect and respect indigenous peoples’ rights in coastal zones and small islands management and environmental protection and management, why isn’t it the same in national forestry law? Because, of course, we understand that in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIPs), there is no definition, but there is a bundle of rights. We can use that. Then I reminded them the comment of the Indonesian delegation when UNDRIPs was adopted. They said that we will have a terrible time in Indonesia to implement this declaration because we don’t have a national definition for indigenous people. But we already have the definition in the environmental law, so that is not the problem with implementing UNDRIPs.

But how do we define indigenous people? It’s easy. It’s a self identification. They map the territories, they show that they exist. At least for AMAN members, we have that information. And they already practise the traditional knowledge to protect their forests.

Agus Purnomo asked us to put all this in a letter to the President. Can you put our discussion in your letter? Of course, why not? No problem. Just to encourage the government – they did it already.

The government has accepted the issue of indigenous peoples, but not in the forestry sector. But the government is one. And the head of the government is the President, not the Ministry of Forestry, right? So AMAN has shown the way. In fact they are already there. If they can only use that in the negotiations.

What we need is commitment from the President to do two things: first to revise the national forestry laws, to be in compliance with international standards and so on; second to have a special national law on indigenous peoples’ rights, recognition and protection. It’s already there! There’s already the commitment in our law. So what’s the problem?

So, I said to Agus Purnomo, why don’t you say to Norway that we will continue our commitment, we will start the drafting of a law on indigenous people in 2011, for example? That’s exactly what’s in my letter to the President.

REDD-Monitor: I assume you’ve seen the article in Development Today, which says that Norway was trying to push Indonesia to include indigenous rights in the Letter of Intent and what the Indonesian government said was this is nothing to do with Norway, we are already in a process of discussion with local groups.

Abdon Nababan: The first thing I want to say is that our letter to the President is a letter from a civil society organisation of Indonesia to our President. This letter was not copied to Norway. I said to Hege [Karsti Ragnhildstveit, Counsellor for

Forest and Climate, Royal Norwegian Embassy, Jakarta], I just sent the letter to my President, from AMAN. She asked to see it. Of course! Because that’s the idea. Because these are the suggestions to my President about what he can do to recognise indigenous peoples through this negotiation.

REDD-Monitor: My understanding of the letter was that most of the first two pages were explaining the situation legally about indigenous peoples’ rights in Indonesia. Correct me if I’m wrong, but you were saying, these are the laws we have recognising indigenous peoples’ rights, so these are the laws you’ve got to follow. So why didn’t the Norwegian negotiators point out to the Indonesian government, you’ve already got these laws, let’s put in the Letter of Intent that you are going to uphold indigenous rights because you’ve got to. It’s already in Indonesian law.

Abdon Nababan: That’s right. It doesn’t make sense for Norway not to talk about this indigenous issue because AMAN has talked about that. Because the letter is all about the rights of indigenous peoples, it’s not about REDD.

Mina Setra: The article in Development Today says that AMAN’s letter might have contributed to the weakness of the Letter of Intent, but for us, Norway should have their own standards of what they demand on rights. We do our things here. But they have to have their own standards to put to the Indonesian government.

Abdon Nababan: It’s our job to advocate, it’s not Norway’s. We have already the commitment.

So what are the contents of the meeting? The meeting was with Agus Purnomo, the the President’s special staff on climate change, and he wanted us to write that directly to the President. That’s all. And the President said we have already met with AMAN. Of course, his staff did already meet with AMAN, officially.

So we wrote our letter in the context of advocacy not in the context of negotiations. There are no negotiations between AMAN and the President of Indonesia related to this.

Mina Setra: Or to Norway. Nothing to do with it. We are a bit surprised that actually we feel that AMAN is being blamed for the weakness of the agreement.

We had nothing to do with Norway-Indonesia negotiations. Norway has to deal with its own standards, to push for rights in the Letter of Intent. They have to take our letter as a support for them to push that.

Abdon Nababan: AMAN also wants a national law to make sure this is happening in Indonesia.

Mina Setra: Development Today didn’t ask me about our letter to the president when they interviewed me.

REDD-Monitor: What’s your opinion about the billion dollar forest deal, what do you think of the Letter of Intent?

Abdon Nababan: Firstly it’s not so surprising for Indonesia. For Indonesia it’s not a big money. Really.

REDD-Monitor: You mean in terms of the Indonesian economy?

Abdon Nababan: Yes, in terms of the Indonesian economy. For them it’s nothing. In terms of natural resources.

I said wow. Suddenly with one billion US dollars, the President of this huge country, Indonesia, signed. That I would appreciate, actually.

Because if you talk about real business, it’s nothing. We’ve had conversion of forest to oil palm plantations. But of course Indonesia is a huge country, with 17,000 islands and 20-30 per cent of the population is indigenous people. And if indigenous peoples’ rights recognised and protected, that’s maybe 60 to 70 per cent of Indonesian land. So for us, this indigenous rights struggle is not about 100,000 people. It’s about millions of people. It’s about maybe 60 to 70 per cent of our national asset.

Of course, for Norway it’s not a lot of money, actually. This is small step, but still it’s important for Indonesia. Not for Norway. This money compared to Indonesia’s natural resources that we have right now.

REDD-Monitor: But there’s no mention of indigenous peoples’ rights in the Letter of Intent.

Abdon Nababan: That’s true. That’s why I say this was very weak of Norway. I say that Norway lost the negotiations on that. What we get from this Letter of Intent though is participation, which is very important. And second, they talk about conflict resolution. A lot of the conflict is based right now on natural resource management, in the context of indigenous rights. That, is quite a big thing for us. We have to change this to be the opportunity. Because we already have our own agenda. We have to advocate for agenda, yes? Because we still talk about the basic rights. It’s very basic. That’s my point.

Mina Setra: It’s true that there have been concerns that there is no mention of indigenous rights. Only in one section it mentions the indigenous people and local communities, as part of the governance system in the implementation of the Letter of Intent.

REDD-Monitor: Have you seen a version of the Letter of Intent in Bahasa Indonesia?

Abdon Nababan: No.

Mina Setra: Not yet, no Bahasa version.

REDD-Monitor: Isn’t that a bit strange? This is an international agreement, for a billion dollars (you say it’s not that much money, but it’s the biggest deal of its kind anywhere, ever), yet the agreement is not available in the local language.

Abdon Nababan: Of course, I know my government. They ratify so many things in international settings. If we ask for an official version in bahasa Indonesian, they’ll just shrug their shoulders and say “Oh, what?”

REDD-Monitor: But it’s quite important to have an official translation, because it’s quite easy to mis-translate.

Mina Setra: Maybe we should ask.

Abdon Nababan: For example, we did not have an official translation of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. So, we translated it and sent that to the government office and they used our translation.

REDD-Monitor: Could you say something more about the proposed Law on the Recognition and the Protection of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which is planned to be written and passed in 2011?

Abdon Nababan: Last year we had a series of meetings with the Regional Representative Council and also with the legislative body in the national parliament. Through this process, it will be one of the national legislative priorities for the period 2010 to 2014. So when we negotiate with the parliament, they asked whether AMAN already has a draft? Well, we haven’t got a draft yet, because we are now in the process of consultation with our members. If AMAN can prepare the draft in 2010, we will then have discussions with the parliament to ask the government to start the process in 2011. So that’s the current status. Now we are working on academic papers and also on the draft. So hopefully at the end of this year we can come to the national parliament for the discussions in the parliament with the government.

REDD-Monitor: If the Norway agreement is signed this year in October, and the indigenous law is signed next year, will the indigenous law also cover the Norway deal.

Abdon Nababan: Of course. That’s one of our purposes. That’s why we gave a copy of our letter to the President to Hege Ragnhildstveit at the Norwegian Embassy. The reason we endorse the deal is because it’s a small window of opportunity and good intentions.

REDD-Monitor: Let’s talk about the two-year moratorium. I have three concerns about this. One is that it doesn’t look like it’s going to affect existing concessions. The second is that it seems now that it may be going to start in January 2011, under the Letter of Intent it’s not clear at all when it’s going to start. And third, there’s an interview this week in the Jakarta Post with Zulkifli Hasan, the Minister of Forests, and he said, more or less, that there already is a moratorium, because he’s not issued any new land concessions that involve converting forests since he became the minister. He said that it is in effect a moratorium. The Letter of Intent is actually saying we’re going to continue for two years what is already happening.

So what’s your view on the moratorium?

Abdon Nababan: For us, now is the time to use this window. That’s going to be the main question for me. Who will be the main players in this one billion US dollar window. We will use that window whether it will be there for five years or ten years. How can we use this billion dollar window to make sure that there is a national law for indigenous people one or two years from now? That’s our main concern here. We know exactly, the one billion dollar window will not address the real problems. So the question is, who will get to that window?

Mina Setra: The Ministry of Forestry may have said that the Ministry of Forestry will not issue any new concessions for forest conversion. But the Ministry of Agriculture is issuing programmes, for example, the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) project in Papua which covers 1.6 million hectares of land and forest. So if they say we will not issue any concessions, what about the other ministries? That’s the big problem in Indonesia because there’s no interrelation between the ministries. There’s a lack of communication and coordination.

Abdon Nababan: That’s also one of the reasons why we work with the Ministry of the Environment. Because if we wait for the Ministry of Forestry, nothing will ever happen.

Our strategy is to strengthen the weakest in the government. That’s why we have our MoU with the Ministry of the Environment [on the Identification of Indigenous

Peoples’ Rights and their Traditional Knowledge] and also with the National Commission on Human Rights [on Mainstreaming Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in

Indonesia]. Because that helps to empower them. AMAN takes the leadership to put ourselves there. REDD is becoming a reason to hate AMAN. We are the main enemy in the whole discussion. But it’s not REDD. We talk about human rights, we talk about the traditional knowledge. We aim to get recognition, protection, respect of indigenous peoples’ rights.

Mina Setra: That’s also the reason for the statement AMAN made at the Oslo Climate Change Conference. We wanted to appreciate the government for its progress on indigenous peoples’ rights issues. We have to admit that there is some progress. Why did we do that? Because we want to encourage them to keep doing the right thing.

Abdon Nababan: Yes, we appreciate the Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Environment, National Commission on Human Rights, but not the Ministry of Forestry. We know that the Ministry of Forestry is the source of the problem. How can you solve the problem with the cause of the problem? Yet at the same time, basically we are talking about forests.

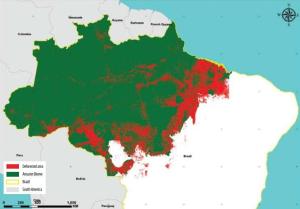

I think I need to say that at present in Indonesia, all over the country, the best forest that we have is mostly in indigenous territories, where the community strong enough to protect the forest. Without recognition and protection of indigenous peoples’ rights there will be no REDD in Indonesia. The real REDD.

We have documented that indigenous people are protecting 500,000 hectares of natural forests. This forest is ready to do REDD. Because the indigenous people have already protected that. They just have to put MRV [measuring, reporting and

verification] in place.

And the indigenous people are not doing REDD because of money. That’s a very important thing. They are doing it for their rights, for the sustainability of the community. Our members say let’s give the money to the government. If the communities report a logging company or an oil palm plantation the government can use the money to remove them. The money is for that. What indigenous peoples need is to have territorial rights. This is not about money for us.

Mina Setra: Why we have to say that, because there are some misunderstandings about our letter. In the letter to the President we have an attachment where we put one million hectares area of forest of indigenous peoples. We also put the name of the community where the forest is protected. Some people thought that we are trying to negotiate a REDD concession with the president. I want to say that that’s not true.

Abdon Nababan: What the attachment to the letter shows is that we are doing our homework. The president has to support what we have already done by reading this attachment.

We were trying to send a simple message to the President but we have realised it’s not a simple message to our side.

REDD-Monitor: There’s a rumour going around that AMAN is getting millions of dollars funding because you’ve signed on to REDD. Could comment on that, please?

Abdon Nababan: That’s not true. That’s really not true. We got money for advocacy and also to prepare our members to do that and the money comes from Norad [the Norwegian

Agency for Development Cooperation]. It’s about US$200,000. And it is not directly to us, the money goes via our own partners. That’s all the money we’ve had.

REDD-Monitor: One last question. What is AMAN’s position on carbon trading? You’ve mentioned it in passing, but what is your position on it?

Abdon Nababan: Actually, we don’t have a position on that. We don’t have an accepted position on that because we don’t know exactly how it works. Of course, we have encountered many resource people on the subject of carbon trading but we are not quite clear what exactly carbon trading is, actually in reality. So it’s difficult to say yes or no.

That’s why I said let’s use REDD to secure the rights of indigenous peoples to manage their resources – that’s our priority right now. There’s no real way that we can feel what the carbon market is. We have to focus our energy, because our energy here is limited here in AMAN. We are a very small office. We have to deal with many things. That’s one of our constraints.

Mina Setra: In our discussions we find that actually in carbon trading the commodity is being created. The market is still being established. We do not yet have the market. And the policy is still being negotiated. So actually, this thing does not yet exist, although people talk about it. What is the carbon market?

REDD-Monitor: But there is already a futures market in carbon. We’ve seen this in Papua New Guinea, where the government has no laws regulating the carbon trade, but the carbon trade started based on trading carbon derivatives. All it takes is someone willing to risk that carbon credits will be exist and be worth a lot of money in, say, 12 months’ time. Companies can start trading carbon derivatives – based on a gamble that carbon credits will be worth more than the paper they are written on. That’s perfectly legal, and happens all the time in commodities markets.

Abdon Nababan: But that’s what I said. How can AMAN, say to our members, community members, that we oppose this carbon market? Or that we agree? We cannot explain this exactly. We can talk about it to a journalist, but to our movement?

We have positions on REDD because we can explain this. Why? We can explain how our position relates to our struggle for our livelihoods. We can explain it well. But for carbon markets, there’s nothing. To understand exactly how it works, we can read books and reports and there’s good information, but can we say this to the communities who have the rights? They are the rights holders of the carbon if you link the carbon to the forest and REDD. And you’ve got to answer them. The rights holders. Not the journalists. That’s our challenge.

To put this in the context of Indonesia we already have some misleading information about the carbon market right now. Not misleading the people but with the head of the regency, head of district, the governors. The only way is to educate people to distribute this information that we already understand, exactly what the carbon market means, to the communities. We cannot go to positions on the carbon market because we don’t know how to communicate about that.

REDD-Monitor: Is there anything else that you want to say on the subject of REDD and Indonesia or indigenous rights in Indonesia?

Abdon Nababan: I think what happens right now is quite dangerous for Indonesia, for the peoples of Indonesia, because the negotiations are actually taking place at the national level. Really, the negotiations are at the international level, not even the national position. It’s only the positions of one of two negotiators. That, I think, is very dangerous.

That’s why in Indonesia right now we are fighting each other. Indigenous activists and environmentalists are fighting. Actually most of their energy right now just to say different things. That’s crazy. It’s dangerous.

Mina Setra: We were discussing this actually. That REDD will really change the situation. We just want to use the opportunity to do the best. If we can sense a little maybe that’s better, but with the government’s behaviour right now, it’s going to be very difficult. Because with other things it’s not changed. For example, mining concessions keep going even the mining concessions in protected forests.

Abdon Nababan: For me, I think of REDD as a strategy. We know that the President cannot change their own ministries, because ministry just has its own space in the state. But now we offer to the President that he can use indigenous peoples rights to change that. So we said why don’t you protect the people who protect the forests and use that to change? If you look at the Indonesian bureaucracy, they have their own space so to take that to have to work through indigenous peoples all the time. Internationally they know that, but they don’t quite fight for that, like Norway, for example. Indigenous rights are very critical to this REDD scheme.

Tags: Financing REDD, Indigenous Peoples, REDD and rights | Category: Indonesia, Norway |

2 comments to “We want to change this threat to an opportunity”: Interview with Abdon Nababan and Mina Setra

- Clive Richardson

This discussion goes to the heart of issues that swirl around unresolved. There has to be direct solutions in terms of Indigenous peoples rights and solutions in terms of enterpise modeling that reflects these rights from grass roots to the International forums. Without this focus to deliver solutions the UNFCCC REDD and REDD + policies are conflict consolidation not resolution guidelines.

- Rupert De Santos

Chris,

very meaningful interview. It is amazing to realize that Abdon Nababan, Mina Setra, Agus Purnomo, and Hege Karsti Ragnhildstveit, have a completely different approach for REDD. Is obvious AMAN’s goal: No indigenous rights duly protected by domestic law, no support for REDD. Of course, the javanese strategy is never to play a straight forward role opposing to REDD. Is clear the opportunity for them is to trade some level of REDD voluntary offset in exchange of land rights recognition and funding. Mrs. Hege of Norway plays the Good Neighbor role, promising 1 billion to the Indonesian Government subject to unclear targets, commitments and obligations. The LoI text is very vague. What a lack of diplomatic touch of Mrs. Hege to do not have offered before a bilingual draft of the LoI to the Government as well as to Indonesian civil society, before the recent signature in Oslo.

In sum, is clear that Indonesia will not see any portion of the 1 billion offer, unless stakeholders really a common vision of the purpose of REDD as international mechanism to reduce GHG emissions.