Jan 21

20140

Foundations, Non-Profit Industrial Complex

911 development aid Ecology effeminization environmentalism Humanitarian Intervention Imperialism militarization of anthropology militarization of entertainment media Military Industrial Complex neoliberalism paternalism

New Book: Emergency as Security–Liberal Empire at Home and Abroad

by Maximilian Forte

Kyle MacLoughlin and Maximilian Forte

“Just as our vision of homeland security has evolved as we have made progress in the War on Terror, we also have learned from the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina….We have applied the lessons of Katrina to this Strategy to make sure that America is safer, stronger, and better prepared. To best protect the American people, homeland security must be a responsibility shared across our entire Nation. As we further develop a national culture of preparedness, our local, Tribal, State, and Federal governments, faith-based and community organizations, and businesses must be partners in securing the Homeland. This Strategy also calls on each of you….Many of the threats we face…also demand multinational effort and cooperation. To this end, we have strengthened our homeland security through foreign partnerships, and we are committed to expanding and increasing our layers of defense, which extend well beyond our borders, by seeking further cooperation with our international partners. As we secure the Homeland, however, we cannot simply rely on defensive approaches and well-planned response and recovery measures. We recognize that our efforts also must involve offense at home and abroad”. (George W. Bush, preface to Homeland Security Council, 2007).

Before we get into an overview of this book, we should provide you with some of the basic information about the book, and how to obtain a copy. Following that, we have a brief introductory overview of the contents and significance of this volume.

About the Book

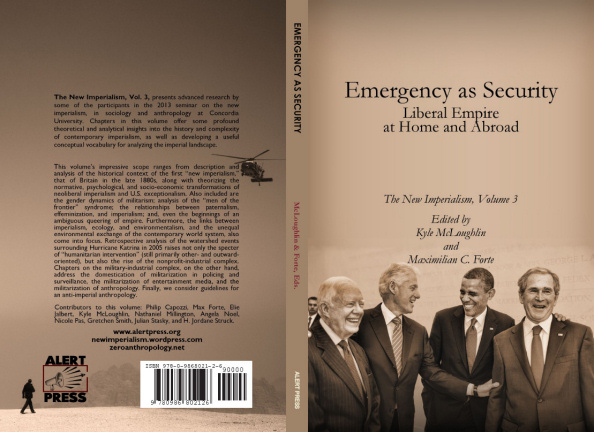

Emergency as Security: Liberal Empire at Home and Abroad (Montreal: Alert Press, 2013), is the newly released third volume in the New Imperialism series emerging from the seminar at Concordia University. The published chapters consist of a selection of some of the best work produced by advanced undergraduate researchers in the seminar, and this is likely our best volume to date. Chapters in this volume offer some profound theoretical and analytical insights into the history and complexity of contemporary imperialism, as well as developing a useful conceptual vocabulary for analyzing the imperial landscape. →

Zero Anthropology

January 18, 2014